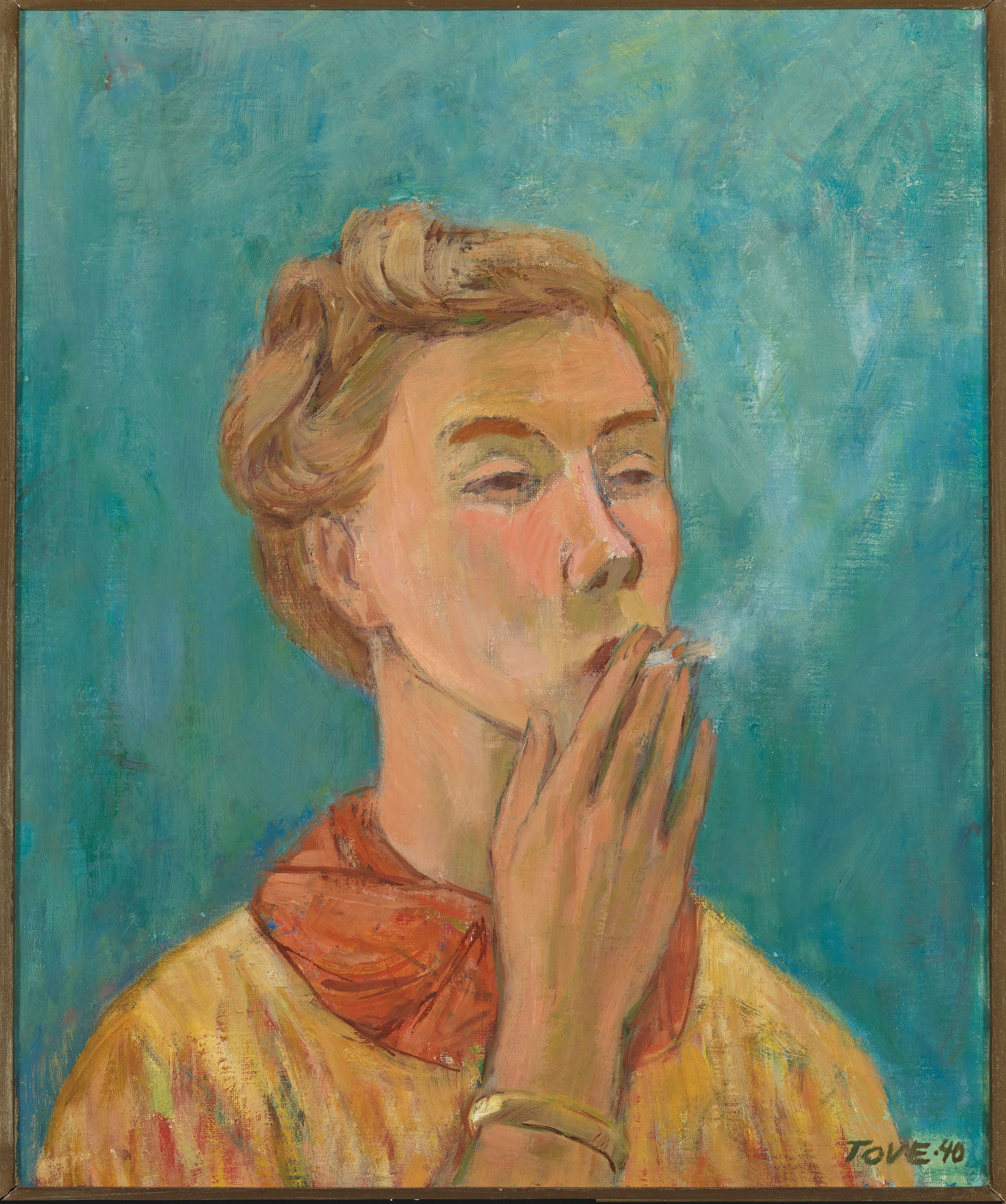

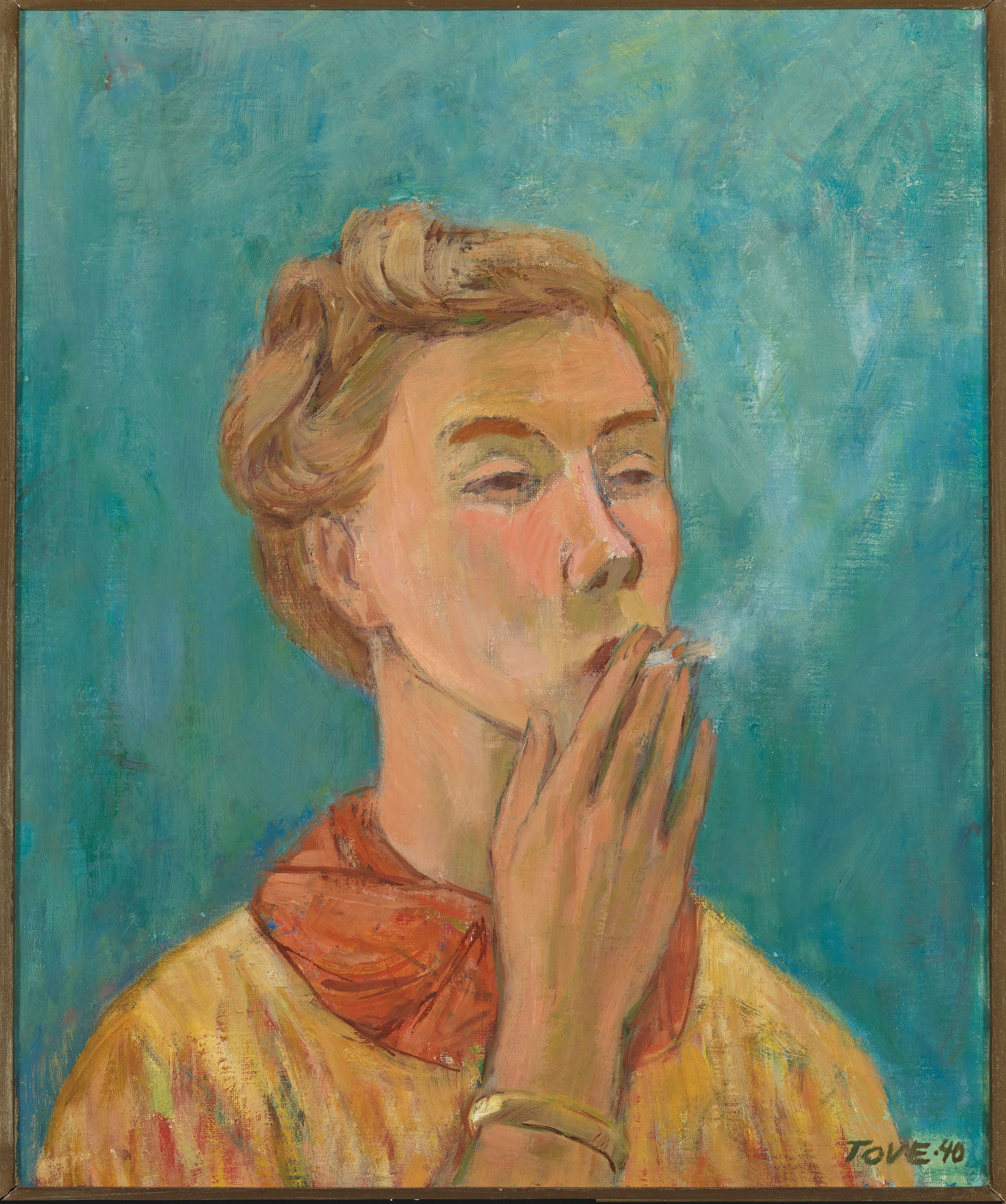

A 1940 oil painting, Rökande Flicka (Smoking Girl), pictures, as the title suggests, a young woman smoking a cigarette. The image draws a close-up of her upper body: the woman’s narrow visage is paired with a slender hand, and the look on her face is one of contained intensity. Yet, she seems nonchalant: her eyes are half-closed, as if she is observing a situation or listening to a conversation from a certain distance. Beige, golden, and ochre hues compose the layers of her skin, her blouse and bracelet; the same tones also define the contours of her boyish haircut. A turquoise-blue background gives the oeuvre depth, while the eyes continue looking, level and profound.

Tove Jansson completed this self-portrait at the age of 26. The painting first found its home at a local tobacco shop, whose owner purchased the work to attract more customers. Later the painting became known as one of Jansson’s pivotal works, both due to the powerful motif of the oeuvre – self-portraits create a central thread traversing Jansson’s oeuvre, and she was always fascinated by the human face – and the context in which the painting was made. A few years earlier, before completing the work, Jansson had finished her art studies in Europe – across France, Sweden, and Finland – and had gradually started exhibiting her work. She could be considered a ready artist now. Nevertheless, the world was turbulent around the aspiring painter: World War II had broken out only a year earlier.

Rökande Flicka (Smoking Girl) is brought together with a selection of paintings and drawings, writings and unseen archives in an extensive, historical exhibition Houses of Tove Jansson. The exhibition explores the multifaceted and prolific career of the Finnish artist and writer Tove Jansson (9 August 1914 – 27 June 2001, Helsinki), the celebrated creator of the Moomins. While providing an extensive overview of Jansson’s creative output, the exhibition also looks at the complexities of this female queer artist, who set out to create her own rules while operating in a male-dominated creative milieu before and after World War II.

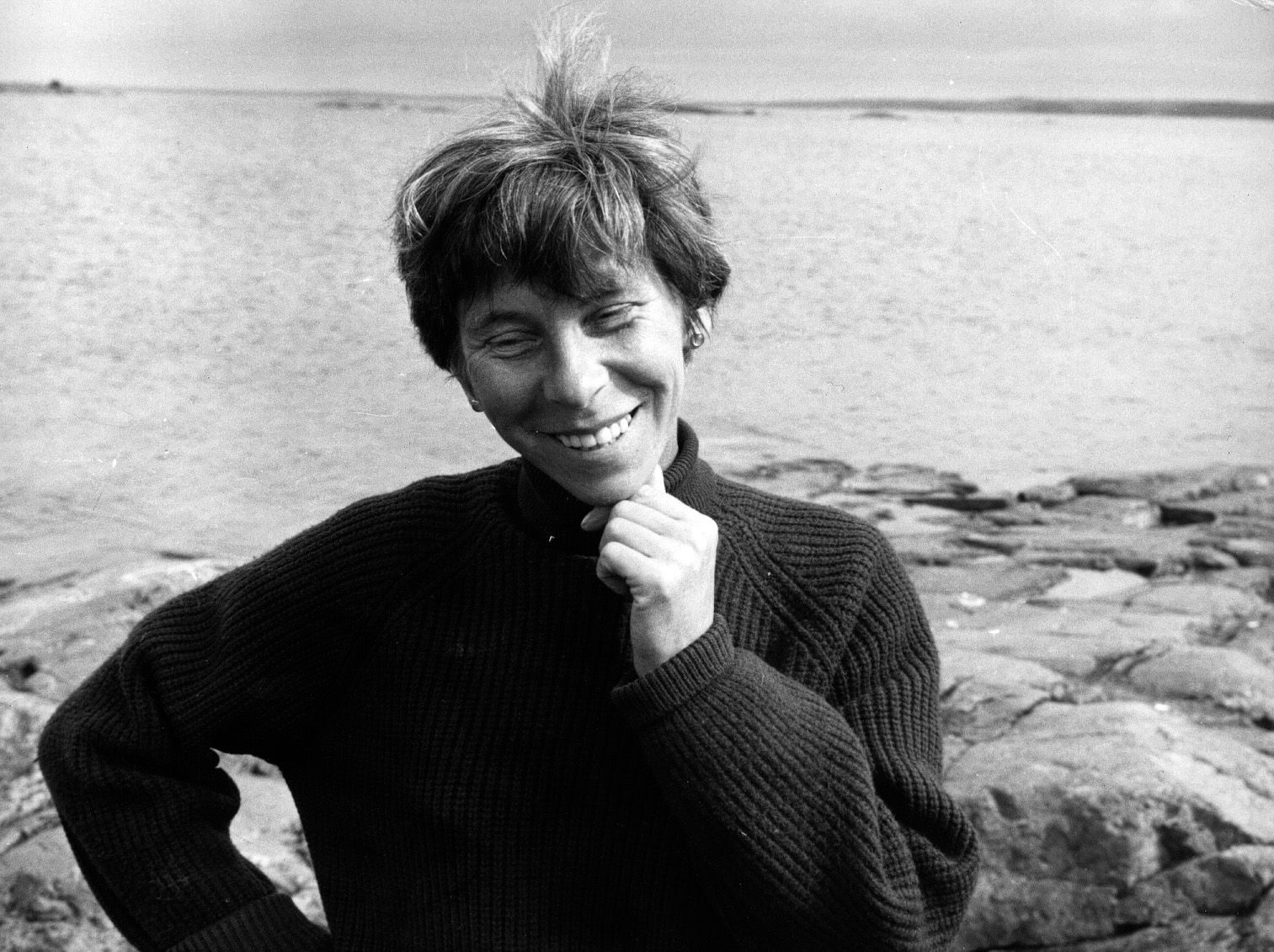

Opening in Paris on 29 September and on view through 29 October 2023, the exhibition is curated by The Community in collaboration with the Tove Jansson Estate and Moomin Characters. The curation draws from the artist’s entire oeuvre, with an expansive selection of works encompassing Jansson’s early childhood drawings and illustrations from the 1920s through her late painterly works completed in the 1970s, as well as writings ranging from the Moomin books to her later adult fiction. The exhibition also features a significant amount of photographic documentation from the Jansson family archives, taken mainly by Tove Jansson’s brother Per Olov Jansson, who was a professional photographer. Additionally, the exhibition includes artworks made by Jansson’s close family circle, notably Signe Hammarsten Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä, each a prolific artist in their own right. The exhibition and the present catalogue comprise a biographical reflection of her life and work while offering a chronological sweep through the various chapters that marked her journey.

Houses of Tove Jansson is the first-ever retrospective exhibition devoted to the Nordic author and painter in Paris, a city that played a pivotal role in both Jansson’s professional and personal worlds. She spent considerable time in the city, and the influence of the metropolis on her output can be seen across her career. As a student, she was strongly influenced by the 1930s School of Paris and the artistic milieu that defined the then-art capital of the world. She returned to her beloved city on several occasions thereafter, both as an experienced writer and artist, notably in 1975 for a residency at Cité internationale des arts.

The powerful writing, wondrous illustrations and paintings, and adventurous, independent way of living that characterised Tove Jansson’s life story have had a lasting impact on readers and followers from across the world. Her legacy remains deeply and equally affecting also for generations of artists. Houses of Tove Jansson presents, for the first time in Tove Jansson’s exhibition history, her work in dialogue with works by contemporary artists. Carlotta Bailly-Borg, Anne Bourse, Vidya Gastaldon, Elmgreen & Dragset, Ida Ekblad, Emma Kohlmann, and Cerith Wyn Evans, all explore – through a wide array of perspectives and practices, via both newly commissioned and existing artworks – the rich, complex and interwoven work and heritage of Jansson. All the invited artists explore and channel, either directly or indirectly, connections to Jansson’s universe: whereas one might have been inspired exploring Jansson’s literary achievements and the unique world of the Moomins, the other might have explored Jansson’s life story, or selected key themes from her life’s journey.

Houses of Tove Jansson takes place in a former print house in the 11th arrondissement of Paris, where different sections of the house and the exhibition space are devoted to presenting various chapters in Jansson’s life in dialogue with a group of contemporary artists. Each section, or room, melds elements from her personal life with her artistic output, two elements that were always inextricably connected and inseparable in her life. Different physical spaces were important to Tove Jansson and were often the focus of her oeuvre. Whether the mischievous Moominhouse reaching towards the skies in Moominvalley or the solitary Klovharun island in the Gulf of Finland, whether her beloved city of Paris or Jansson’s intimate atelier in downtown Helsinki: all these sites have left a profound trace in Tove Jansson’s work and life. And also vice-versa: as she travelled across these different worlds and times, Jansson always left highly personal imprints on the places she came across. These spaces, whether imagined or tangible, have been guiding us in the exhibition-making and the journey leading up to the present show.

The journey started, in a sense, a long, long time ago. The Moomins and their beloved creator Tove Jansson were an essential part of the childhood of anyone who grew up in Finland in the 1990s. If the Moomin books hadn’t already been brought home from the the local library, the hippopotamus-like, chubby white creatures were introduced to one’s living room and visual sphere through the popular Japanese TV animation adaptation. When we first started to work on this exhibition two years ago, the occasion seemed at once daunting and marvellous. Daunting, just because of the sheer volume of Jansson’s many achievements (it is challenging to know even where to begin in approaching her work). Marvellous for offering an excuse to re-read the Moomin books late into the night at an adult age. Over the course of the past two years, curator Sini Rinne-Kanto immersed herself in Tove Jansson’s life: exploring her archives and work – a real Gesamtkunstwerk – both in her atelier space and her island, or defying the capricious September storm when trying to reach her sanctuary and island Klovharun in the Gulf of Finland.

The first Moomin book, Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (The Moomins and the Great Flood) was published in 1945 as an escapist fable in the context of the War. While we continue today to live among the ruins of 20th-century ideologies and witness the rise of fascist and nationalist regimes, social inequality, and environmental problems on a planetary scale, it is interesting to look at Jansson’s oeuvre and life from a transhistorical perspective. She always managed to deal with darkness and weighty matters – such as wars – with intelligent intimacy and humour. What continues to move us in and through her work is the universality and the humanity it offers while also silently pursuing a revolution against heteronormativity, against rules and authority, against authoritarianism. Houses of Tove Jansson provides a journey across the entire oeuvre of this deceptively radical children’s author, who relentlessly sought to break the boundaries set up on her path.

“Dear Jansson san

You were going to go on a great long journey, now you’ve been travelling more than six months.

I think you’ve come back again.Where did you go, my Jansson san, and what did you learn on your journey?”

– Excerpt from Tove Jansson: Travelling Light

Tove Jansson grew up in a family where art was the nucleus of life, the only path one should choose. Her mother Signe Hammarsten (1882–1970), originally from Sweden, was one of Finland’s most talented illustrators, a woman whose works adorned books, magazines, and stamps across the Nordic countries. It was in her mother’s arms that Tove Jansson learned to draw and acquired a gift for creativity. Ham – as everyone called Signe Hammarsten – was Tove Jansson’s first and most important teacher, and the two remained extremely close throughout their lives.

Paris played a decisive part also in Jansson’s parents’ lives. In 1910, Signe Hammarsten met her future spouse Viktor Jansson (1886–1958) at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Montparnasse, a school where they were both studying at the time. As the young couple started to expect their first child – Tove – in Paris, they decided to move to Helsinki, where Viktor Jansson established himself as a well-known sculptor. Boel Westin astutely describes her father in her biography of Jansson: “His life became to a large extent a story of competitions, prizes won and lost, triumphs and disappointments.”1 While supporting her husband’s artistic devotion, Signe Hammarsten renounced her dreams of becoming an artist herself, and instead focused on providing the family with a much-needed steady income while doing illustrations for various clients. Observing this role division in her family deeply impacted how Tove Jansson considered the role of women and the importance of freedom, both of which remained a central topic throughout her life.

Jansson, the eldest of three siblings, started her art studies at the age of 16 at the Stockholm Technical School and continued them a few years later by enrolling at the Drawing School of the Finnish Art Society at the Ateneum. She also attended art schools in Paris, at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Atelier Adrien Holy, and the eminent École des Beaux-Arts. Jansson portrays her colourful and vivid experience at the Beaux-Arts in a 1938 short story titled “Quatz’ Arts”, which appears in English for the first time in the exhibition catalogue, alongside the short story “The Beard”. Jansson’s early paintings from this period, especially those completed before the outbreak of World War II, often featured paradise sceneries combined with a magical and enigmatic fairy-tale atmosphere. Adorned with compelling colours and contrasts, her work at this time even occasionally flirted with surrealism. Her output during this era reveals Jansson’s ultimate quality as an artist: she was first and foremost a storyteller, and her painterly expression was an interplay between the quotidian and the imaginary. In the 1930s, while she was busy finishing her studies and working on her portfolio, she also travelled across Europe. Italy, France and the post-impressionism that was fashionable at the time had a major influence on her work, which centred on colour, form, light, and implicit storytelling. The young artist became the subject of an increasing amount of attention: she gained various commissions for public projects and solo exhibitions both as a painter and a celebrated muralist.

Jansson’s work encompasses love and friendship, loneliness and solidarity, but also, extensively, politics and society. The chaos and destruction brought by the war years were extremely difficult for the uncompromising pacifist. This period was characterised by constant worries about friends, lovers and family members. When the War broke out, Jansson was 25 years old and still living at home with her family, including her brother Per Olov Jansson who would spend time, on and off, at the battlefront. The dynamic within her family was coming under strain. Jansson’s relationship with her father, who disapproved of her lifestyle and choices – essentially that she showed no signs of marrying and settling down – was increasingly challenging. One of Jansson’s key paintings from this period, Familjen (Family) (1942) reveals this difficult dynamic: all the family members are shown tired, silent and constrained, with Jansson in the middle in a black attire of mourning. The work is, essentially, a portrait of a war.

Many central painterly themes of modernism, such as self-portraiture, still-life and urban scenes were also recurrent in Jansson’s work. The importance of different interiors and a sense of place remained an important motif in her oeuvre. She often painted rooms – either her own atelier space or hotel rooms where she stayed during her frequent travels. The pivotal moment in Jansson’s quest for identity, freedom and sexuality occurred after the war when she finally found a room of her own. Her atelier in downtown Helsinki, in which she both lived and worked until the end of her life, became a place specifically for her to exist in the world. The conditions were harsh: the atelier was entirely destroyed by bombings during the War.

In a letter to her dear friend Eva Konikoff, Jansson enthusiastically describes this first permanent atelier apartment:

It’s magnificent here, don’t you agree? A tower room, as lofty as a church, nearly eight metres square, with six arched windows and above them some little rectangular ones like eyebrows, up near the ceiling. Piles of mortar and cracks here and there, because it’s still not fully repaired after the bombing, and in the midst of all the debris, an easel. A huge Art Nouveau fireplace with ornate scrolling and a comical old door with red and green glazed panels.

— Tove Jansson in a letter to Eva Konikoff, 1944

The letter exchange between Jansson and Konikoff demonstrates Jansson’s devotion and great care in regard to the genre of letter correspondence. Konikoff, a Russian-Jewish photographer, spent a considerable amount of time with Jansson in the same artistic circles, until she fled to the United States when the war broke out. The two exchanged about a hundred letters from 1941 to the end of the 1960s and these letters can be read as a sort of diary with occasional drawings, following the patterns of a natural conversation. After the Moomin books were translated and warmly welcomed internationally, Jansson received an average of 2,000 letters across the world per year from her fans – usually signed by children – and famously took great care and detail in answering all these letters personally. She also used the form of letter correspondence in her later fiction work, such as the short story ‘Correspondence’ (1987) which appeared as part of the book Travelling Light, in which the author exchanges letters with a Japanese reader and fan named Tamiko Atsumi.

Jansson referred occasionally to wartime as the “lost years” of her life. However, they also seem to have been extremely productive and pivotal considering the development of her work. In parallel with her artistic practice, Jansson was earning her living by making illustrations for books, magazines and postcards, following in the footsteps of her mother Ham. An important employer for both of them was the satirical political magazine Garm. During World War II, Jansson was Garm’s primary cartoonist, openly criticising the enemy powers and high-ranking political leaders, such as Hitler and Stalin, under her own name. Over several years, she illustrated around a hundred covers for the magazine (her first illustrated cover appeared in 1935) and over five hundred images and caricatures. Garm illustrations represent an important chapter for Jansson not only in communicating her pacifist mindset and vocal output, but also because it is on the magazine pages that the first snork-like, round figures with long stouts appear in print – a prelude for the Moomins.

The idea came to me all at once, as is usually the case. (I just hear a faint ‘click’, and there it is.) Given a Moomin and a place, and there must follow a house. I was going to build a house with my own hands, a house exclusively my own!

My first Moominhouse arose with mysterious speed. That must have been due to inherited ability, but also to talent, good judgement and a sure taste. But one mustn’t indulge in self-praise, so I’ll only give you a simple sketch of the result.

It was quite a small house, but tall and slender as a Moominhouse should be, and adorned with several balconies, stairs, and turrets. The hedgehog lent me a fret-saw to do the pine-cone pattern on the verandah balustrade.

– Muminpappans bravader. Skrivna av honom själv (The Exploits of Moominpappa) (1950)

The Moomin books, a series of twelve that were written and published over more than two decades (1945-1977), established Jansson’s career as an internationally known author. Her personal life often nourished and inspired the literary themes: the scenes and characters had a habit of mirroring the author’s personal life. Gradually, book by book, the themes and the tone in which they are handled evolve – from the disaster-prone adventures explored in the first books, towards a greater development of the inner journeys of their characters. Trollvinter (Moominland Midwinter) (1957), can be read as this sort of coming-of-age story, in which the author introduces to the readers the important character of Too-ticky, who was inspired by Tuulikki Pietilä (1917–2009), Jansson’s life partner. Before meeting Pietilä, Jansson had already started to explore queerness, having had several same-sex relationships during and after the war, notably with the theatre director Vivica Bandler (1917-2004). Jansson worked with Bandler on the first Moomin play, Comet in Moominland, shown at Helsinki’s Swedish Theatre in 1949. The two were the inspiration behind the respective characters of Thingumy and Bob, who first appeared in Trollkarlens hatt (Finn Family Moomintroll) (1948), carrying a strange suitcase and speaking a secret language of their own. Elsewhere in the exhibition catalogue, writer Hannah Williams writes about the queer side of Tove Jansson’s life in the essay ‘Just Linger for the Pleasure of It’.

Following the worldwide fame and success of the Moomin book series and the comics, Tove Jansson gradually turned her attention to writing for adults and exploring other literary formats. Bildhuggarens Dotter (Sculptor’s Daughter) (1968) is her first book destined for adult readers: narrated from a child’s point of view, it is written in the form of connected short stories, reflecting her own experiences growing up in a bohemian home and spending summers on islands. Her later books Den ärliga bedragaren (True Deceiver) (1982), and Rent Spel (Fair Play) (1989) both demonstrate the considerable development of her literary tone: the hint of darkness that was earlier present in her children’s books through tangible disasters and threats is now expressed through more complex characters and literary strategies.

We dreamt of what the cottage would look like. It would have four windows, one in each wall. In the south east we made room for the great storms that rage in across the island, in the east the moon would be able to reflect itself in the lagoon, and in the west there would be a rocky wall with moss and polyps. To the north one had to be able to keep a lookout for anything that might come along, and have time to get used to it.

— Anteckningar från en ö (Notes from an Island), Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä, 1996

Islands, archipelagos and the sea have played a special role in Tove Jansson’s life and work since an early age. Winters were spent in downtown Helsinki, and summers outdoors in the archipelago in the Gulf of Finland. Jansson and Pietilä built their own summerhouse in the mid-60s on an island called Klovharun, which became their sacred haven, providing much-needed calm and privacy for the couple. In spring, as soon as the ice broke out the pair left the city, returning to Helsinki only in October.

Jansson’s fascination with regard to natural phenomena and changes in the weather – undoubtedly inspired by the summers spent outdoors – greatly affected Jansson’s writing and paintings. One part of her genius was to create a language out of the landscape that was so dear to her: the solitary Nordic winters and endless festive midsummer nights, while gazing at the rock formations and the sandy beaches. While the tone in her later adult fiction is more contemplative with respect to nature, the Moomin adventures present a more catastrophic vision, courtesy of the lurking dangers often to be found around the corner: the comets threatening the planet and the threat of impending drought, which can be read almost as admonitions of climate change.

On the fifth of October the birds stopped singing. The sun was so pale that you could hardly see it at all, and over the wood the comet hung like a cartwheel, surrounded by a ring of fire.

Snufkin didn’t play his mouth-organ that day. He was very quiet and thought to himself, “I haven’t felt so depressed for a long time. I usually feel sad, in a way, when a good party is over, but this is something different. It’s horrible when the sun has gone and the forest is silent.”

— Kometjakten (Comet in Moominland), Tove Jansson, 1946

On the pages of the exhibition catalogue, you can find Jansson’s short story “The Island”. Originally published in the Finnish travel magazine Turistliv i Finland (Tourist Life in Finland) in 1961, it can also be read as a sort of prelude for Jansson’s eminent novel Sommarboken (The Summer Book). Published in 1972 and now celebrated as a classic of Nordic literature, The Summer Book is one of her most acclaimed adult fiction books. A meditation on love, summer and life, it follows a grandmother and granddaughter meandering on a tiny island. Jansson’s adult fiction continues today to inspire generations of writers and creatives: loosely inspired by the novel, the author Kate Zambreno has written a fictive essay, Summer, for the exhibition catalogue.

Jansson continued the habit of spending summers on the archipelago for nearly three decades. The summer of 1992 was the last one that they spent in Klovharun. It has been said that during this ultimate boat trip, Tove Jansson never looked behind to have a last glance at her island. Anteckningar från en ö (Notes from an Island) (1996) is Jansson’s penultimate book that she wrote when she was over 80 years old, with illustrations by Tuulikki Pietilä. Offering a moving homage to the island, she writes:

And last summer, something unforgivable happened: I started to fear the sea. The giant waves no longer signified adventure, but fear, fear and worry for the boat and all the other boats that were sailing in bad weather. [...] We knew that it was time to give the cottage away.

In parallel with the new exploration of literary genres, Jansson’s paintings, from the 1950s onwards, evolved into something more simplified. Still lives, rock formations and stormy seas were frequent motifs. Sometimes the work even edged into abstraction, as in her 1968 oil painting Abstrakt komposition (Abstract Composition). However, such tendencies didn’t find a permanent place in her practice, as she was someone who always sought to convey a story.

Her 1975 oil painting Självporträtt (Self-Portrait) is one of the closing works in Houses of Tove Jansson. Made during her residency at Cité internationale des arts in Paris, the work completes a full circle within her painterly oeuvre: after having briefly flirted with abstraction, Jansson returns to a figurative self-portrait at the age of 61. It is one of her last, and strongest, works. As in the opening work Smoking Girl, we are presented once again with a close-up portrait of the artist. Her visage has a serenity brought about by her use of rough brushstrokes, which create a psychological inner portrait of the matured artist.

In the opening story from the collection Resa med lätt bagage (Travelling Light) (1987), “An Eightieth Birthday”, a young, rather naive couple, a woman and a man, is invited to the former’s grandmother’s birthday. The grandmother, the matriarch of the family, is an artist who has always painted the same trees, no matter the aesthetic fashion in play elsewhere in the world. Two guests of the party, rather disarrayed artists past their best, give the young couple a lesson on life and art:

“You know, it was all Informalism then, everywhere; everyone was supposed to paint the same way.” He looked at me and could see I didn’t understand. “Informalism means, roughly, painting without using definite forms, just colour. What happened was that a lot of old, very talented artists hid away in their studios and tried to paint like young people. They were afraid of being left behind. Some managed to do it, more or less, and others got lost and never found their way back. But your grandmother stuck to her own style and it was still there when all that other stuff had had its day. She was brave, or maybe stubborn.” I said, very carefully, “Or maybe she could only paint her own way?” “Marvellous,” said Keke. “She simply had no choice.”